I. Introduction

African Liberation Day (25 May) marks the founding of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, a crucial milestone in the continent’s struggle against foreign subjugation. After over a century of arbitrary colonial partition and despite neo-colonial efforts to continue a policy of “divide and conquer”, the newly liberated states of Africa succeeded in forming an organisation whose goals and principles expressed a clear anti-colonial character, corresponding to the interests of Africa as a whole: political sovereignty, non-interference, the complete eradication of all forms of colonialism, and the aspiration for unity and solidarity amongst the people of Africa.

The OAU also reflected the challenges and contradictions facing liberated Africa. The unity that had been forged during the resistance to colonialism soon gave way to a differentiation process within and between the newly liberated states. Under the leadership of which social classes and upon the basis of which mode of production were the new African states going to develop? The founding of the OAU was a compromise between two factions crystalising across the continent: revolutionary democracy, led by figures such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Sékou Touré of Guinea, and Modibo Keïta of Mali, strove to unite Africa upon a firm anti-imperialist and popular basis, while reformist and comprador forces, represented by leaders such as Senegal’s Léopold Sédar Senghor and Ivory Coast’s Félix Houphouet-Boigny, sought to keep the region within France’s imperialist orbit and hinder socialist-oriented development in Africa. It was these contradictions that the West tried to exploit in order to keep the continent divided. Both the achievements and limitations of the OAU – and the African Union that succeeded it in 2002 – reflect the contested nature of these institutions.

Many of the questions deliberated at the first OAU summit in May 1963 are still at the centre of debates today. How can the colonially imposed balkanisation of Africa be overcome? Would it be possible to create a customs union or even a common currency for the continent? Do foreign military bases have a place in Africa? Is non-alignment an appropriate foreign policy as the international balance of power is shifting?

To mark African Liberation Day, this dossier explores Africa’s long struggle against one of its greatest foes, French imperialism. Through various political, economic, and military mechanisms, France has been able to maintain a tight grip over its former African colonies while presenting itself as their benevolent big brother. The three contributions to this dossier examine previous and current attempts to break out of these relations of dependency and subordination.

Nathan Macé investigates the crucial period directly prior to and following independence in the French colonies, when the international communist movement played an important role in early attempts to create unity amongst anti-imperialist forces in Africa and Europe. The pan-African trade unions and political parties that arose out of these initiatives were soon undermined by political machinations from France – a pattern that would be repeated in the decades to come. Macé also points to how reformism in the European working-class movement eroded internationalism and anti-imperialist solidarity with the former colonies.

Georges Hallermayer explains how West Africa’s continued monetary dependency on France cripples the local population while enriching foreign monopolies. He provides an overview of past attempts to break out of France’s neo-colonial currency, the CFA franc, and argues that a new attempt is now being undertaken by an emboldened national bourgeoisie, which is replacing comprador regimes in many West African states. He highlights the potential paths to monetary independence that are currently being debated in the region.

Raphaël Granvaud focuses on the 2023 popular coup that overthrew the corrupt regime in Niger, which had appeared to be the West’s most secure bastion in the Sahel after similar coups had overthrown French-backed governments in Mali and Burkina Faso. In the wake of NATO’s intervention and destabilisation of Libya in 2011, conflict spread throughout the Sahel, and Western states used this as a pretext for increasing their military presence in the region. The failure of these missions and the continued economic exploitation of the region has given rise to a popular demand across the Sahel: “La France, dégage!” (“France, get out!”)

A shared conclusion amongst progressive forces in the region is that, while a new anti-imperialist impulse is undoubtedly sweeping across West Africa, the path ahead is long and full of contradictions. The political establishment in France is now debating how to refine its “Africa policy”, so as to prevent a further loss of influence in the region. The debate in West Africa about the feasibility of replacing the CFA franc is fraught with discord and division. And, while European militaries are withdrawing from the region, the US’s Africa Command maintains a strong foothold in the states neighbouring Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. As the West African Peoples’ Organisation concluded in May 2024: “Patience is necessary. Change is coming. But it is coming at its own pace.”

Matthew Read, Zetkin Forum for Social Research

25 May 2024

II. The Communist Study Groups in France’s African Colonies

Nathan Macé, 21 May 2024

Introduction

The end of the Second World War inaugurated a new era of the 20th century: the old European colonial powers had been greatly weakened, a new socialist world system had emerged across Asia and Eastern Europe, and the national liberation movements in Africa and Asia were invigorated with a new dynamic. Aspirations for national independence clashed with the fierce colonial apparatus that sought to maintain control over territories, resources, and populations. Yet, in just under twenty years, this hold over Africa and Asia collapsed, culminating in a decade in which a multitude of territories wrested their independence. The factors behind this shift are many and complex, but one in particular interests us in this article: the Groupes d’études communistes (GEC, Communist Study Groups). These organisations are often overlooked in historical accounts of Africa’s independence movements, but they played a role of some importance. French communist historian Jean Suret-Canale, who was directly involved in the GECs during the 1940s-1950s, is the author of a short book on the subject, Les Groupes d’études communistes (G.E.C.) en Afrique Noire, which forms the basis of this article. In his book, Suret-Canale looks back at the GECs, their organisation, membership, and the impact they had in the former French colonies. It is an invaluable account since sources on the subject are very rare. This article examines the experience of the GECs, the colonial context that led to their establishment and the impact they had on the independence and trade union movements in Africa.

Left-wing parties and the French colonial context

“If you do not condemn colonialism, if you do not side with the colonial people, what kind of revolution are you waging?”, declared Nguyen Aï Quoc at the Tours Congress of the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) in 1920. The man who would become famous as Ho Chi Minh was the only representative of the “colonised” in the French colonies. His intervention, at this pivotal event for the French Left, exemplified the attitude of the colonised peoples towards the French Left at the time. The latter – which in 1920 split between the reformist Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière (SFIO) and the revolutionary Section française de l’Internationale communiste (SFIC, later the Parti communiste français) – had a rather ambivalent stance towards the colonies of the French empire.

Indeed, for a long time, SFIO and SFIC policy on the colonies was marked above all by a form of political opportunism and disinterest in the colonial question. While some militants, such as Paul Louis, theorised the need to discuss the fate of the populations of the colonies, many members showed little interest in them, preferring to focus on the fate of the working proletariat in metropolitan France. The first turning point came in 1920, however, when the split at the Tours Congress was triggered by the desire of the majority of the SFIO to join the Third Communist International (Comintern). Political parties seeking to join the Comintern were required to commit themselves to twenty-one conditions: one of which, the eighth, related to the anti-imperialist and national liberation movements in the colonies.

“Parties in countries whose bourgeoisie possess colonies and oppress other nations must pursue a most well-defined and clear-cut policy in respect of colonies and oppressed nations. Any party wishing to join the Third International must ruthlessly expose the colonial machinations of the imperialists of its “own” country, must support—in deed, not merely in word—every colonial liberation movement, demand the expulsion of its compatriot imperialists from the colonies, inculcate in the hearts of the workers of its own country an attitude of true brotherhood with the working population of the colonies and the oppressed nations, and conduct systematic agitation among the armed forces against all oppression of the colonial peoples.” – Extract from the Terms of Admission into Communist International (July-August 1920)

In the years that followed, the French Communist Party (PCF), as the SFIC was renamed in 1921, embarked on numerous campaigns to oppose and denounce French colonial policy. It opposed the French intervention in the Rif War in 1924 for example, organising strikes with hundreds of thousands of workers to denounce French actions. The Second World War and the rise of fascism in Europe, however, saw the PCF shift its focus away from the colonies once again, as all forces were now concentrated on the fight against the fascists.

GECs in Africa

The origins

While the PCF upheld the fight against French colonialism from metropolitan France, the question soon arose as to how to coordinate this with the struggle of the colonised populations. Indeed, they were the ones suffering directly from French colonial policy. There was in fact a growing number of requests from the colonies seeking to join the PCF. The Party, however, did not want to create local sections of the PCF in the colonies, but rather sought to encourage the emergence of independent parties specific to each territory, built by local cadres with local knowledge. This idea can be found in a letter written by Raymond Barbé, director of the PCF’s colonial section, to Saïfoullaye Diallo, who would later become a minister in independent Guinea. When Diallo had asked to join the PCF, Barbé replied that this would be inadvisable, but this “does not prevent those who wish to do so, because of their sympathy for communist ideas, from grouping together in Communist Study Groups, where they can further their communist education and political training with a view to best serving the orientation and aims of their party”.

During the 1940s, more and more Europeans living in Africa joined “patriotic associations” (such as the Groupement des victimes des lois d’exception de l’AOF, the Groupement d’Action Républicain which became the Front National, the Amis de Combat, France-URSS, etc.), which sought to bring together activists around common themes such as anti-colonial education and resistance to the Vichy colonial regime. While these associations tended to be left-leaning, they consisted exclusively of Europeans (the colonial administration being strictly opposed to any association between natives and Europeans). They thus represented only a small proportion of the population in the colonies. These associations, which gradually disappeared after the Second World War, were an embryonic form of the GECs. It was here that certain militants and organisers met before setting up the first GECs, which gradually replaced the patriotic associations in the more left-wing circles of European society in Africa after 1945.

Although the first GECs began to form unofficially in the early 1940s, it wasn’t until 1945 that a real movement was launched in Africa, notably after the publication of a circular by the PCF secretariat in September 1945, which formalised the desire to create “Groupes d’Études Communistes”. In the same circular, the PCF set out a number of objectives for these organisations: firstly, the GECs should open up to African populations and no longer be limited to a European membership; secondly, the trade unions that already operate in Africa should be united and the separation between European and African unions must be overcome; finally, the ultimate goal should be to create new democratic and progressive political parties that could be the bearers of a liberation movement. The programs of these parties should be inspired by the new program of the Conseil national de la Résistance (CNR).[1]

The creation of the GECs was thus prompted by several factors: firstly, ongoing requests from African militants to join the PCF; secondly, the presence of patriotic organisations in Africa, which provided a rallying point; and thirdly, theoretical inspiration from Joseph Stalin. On 18 May 1925, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the USSR gave a speech to students at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow, in which he explained the strategy to be adopted in colonised countries where there was practically no proletariat to lead the struggle for independence and revolution.

“We have now at least three categories of colonial and dependent countries. Firstly, countries like Morocco, which have little or no proletariat, and are industrially quite undeveloped. Secondly, countries like China and Egypt, which are under-developed industrially, and have a relatively small proletariat. Thirdly, countries like India, which are capitalistically more or less developed and have a more or less numerous national proletariat.” – Joseph Stalin

According to the PCF’s analysis, many West African countries fall into the first category, as they were essentially agricultural, with no major industry and therefore no real proletariat. Communist militants should therefore set about uniting their forces to create a popular anti-imperialist front.

The GECs were not immediately repressed by the colonial administration: at the time, the communists were one of the leading political forces in mainland France, enjoying great popularity thanks to their role during the resistance to and the liberation from Nazi occupation. The PCF was active in all governments until 1947.

In Africa, GECs began to develop gradually. But, like the patriotic associations, they met with only moderate success at first, and were made up almost entirely of Europeans. Soon, however, African intellectuals began to take up contact with the GECs, and their influence grew. Little by little, more and more African workers joined these organisations, sharing a common distrust of the colonial administration and the actions of the reformist SFIO. Each GEC operated autonomously, only communicating with the secretariat of the PCF’s colonial section and with each other at a regional level. Their activities were manifold: organising political discussion circles, hosting theoretical training sessions, holding evening classes (as with the creation of a Université Populaire Africaine in Dakar), writing and distributing newspapers, organising demonstrations, etc. The GECs also regularly wrote “reports” to the metropolitan headquarters, in which they described the economic and social situation in their region. The GECs were spread throughout the continent: in the Republic of Congo, Senegal, Gabon, Chad, Cameroon, Niger, Benin (formerly Dahomey), Burkina Faso (formerly Upper Volta), and much further afield (Mauritania, Madagascar and even a little in the Pacific).

But the GECs also exhibited flaws and weaknesses. First and foremost, their existence reflected the PCF’s somewhat paternalistic view of African militants, whom it did not consider ready to lead the struggle for independence. This paternalism was illustrated by the fact that the vast majority of GECs had been set up and were for a time run by European militants. As the African independence movements were still in the process of being structured, these cadres provided a certain ‘militant rigour’. The link between the GECs and the PCF’s central structure in metropolitan France was mainly due to the fact that the PCF was the ‘political’ relay in Paris for African demands from the colonies. As the PCF’s central policy shifted towards strong support for independence movements in the colonies, a more important role was given to African militants, who gradually took control of the GECs. Nevertheless, the Groups were ultimately fragile structures, heavily dependent on the most active members running them. As a result, it was not uncommon for certain GECs to go dormant or even disappear altogether if one or two key members left. What is more, after the popular front government in metropolitan France broke down in 1946/47, the colonial administration became increasingly repressive towards these cells of communist political agitation, in which collaboration between Europeans and Africans was increasing.

One example of this repression concerns the Dakar GEC, of which Jean Suret-Canale was a member. In February 1949, when a workers’ strike was organised to demand higher wages, Senegalese Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) union leader Abbas Gueye was prosecuted for leading an “illegal strike”, while Suret-Canale was arrested in the early hours of the morning and deported on the first plane back to metropolitan France. Following a protest movement against these decisions a month later, many activists were arrested, dismissed, and deported. This method of expelling European GEC members to the mainland sought to destabilise the internal organisation of the GECs. While this was often initially effective, it also contributed, almost ironically, to the strengthening of autonomy amongst the African activists, who then took over leadership roles or turned to the new progressive parties.

But the repression against the GECs and against the labour movements more generally also took more violent and dramatic forms. At the end of September 1945, armed settlers fired on strikers demonstrating in the streets of Douala (Cameroon), killing hundreds of people. Following these events, several European members of the Yaoundé GEC were arrested and deported to France, marking the end of the local Group. Local African militants then reconstituted their own GEC in 1948.

The GECs and the Rassemblement démocratique africain (RDA)

In October 1946, at a congress held in Bamako (Mali), the Rassemblement démocratique africain (RDA) was born as a pan-African federation of major parties on an anti-colonialist basis. Despite many attempts to torpedo the congress (several leading politicians, such as Léopold Sédar Senghor, opposed the event at the behest of their SFIO allies), the delegates were successful at creating the new party, thanks in no small part to the help of the PCF, which hoped the RDA could become the anti-colonial united front it had long been seeking to promote in Africa. Pro-colonial forces did not take kindly to this new anti-imperialist revival. The SFIO, particularly fearful of losing influence in Africa, pursued a divide and conquer tactic by, for example, bribing certain political leaders to oppose the RDA. The PCF’s parliamentary group, meanwhile, grew much closer to the leaders of the pan-African RDA.

“With an appearance of reason, they (the colonists) denounced the fact that we were elected only by a minority of Africans. But it wasn’t us who had established the electoral college. It was the colonists… We therefore asked for the support of a large African movement, a large popular movement that could support our action in the French Parliament, and extend the action that we ourselves had just carried out in diversity… But we had counted without the impetuous of division….” – Félix Houphouët-Boigny, first president of the RDA

The role of the GECs in this process cannot be underestimated, as many of the big names who took part in the Bamako congress had been members of Marxist groups at the time. Among them were Léon M’Ba (GEC of Libreville, future President of Gabon), François Tombalbaye (GEC of N’Djamena, future President of Chad) and Modibo Keïta (GEC of Bamako, future President of Mali). A few months before the congress, several GEC leaders had visited the PCF headquarters in Paris to discuss the possibility of creating a united front in French Africa. The PCF helped these African militants to draw up a manifesto, which the GECs then used to convince African leaders to join the RDA.

In the years that followed, the GECs continued to maintain links with the RDA, notably through their common membership. But in fact, from 1946 and following the creation of the RDA, the GECs withdrew from local political activism to concentrate on their primary activity: training and educating the next generation of militants. Their links to the PCF and RDA meant, however, that they remained targets of colonial repression. On 13 April 1950, for instance, the US-RDA (the Senegalese section of the RDA) organised an anti-Franco demonstration in front of the Spanish consulate in Dakar. Thirty-eight members of the RDA and GEC were subsequently arrested and seven sentenced to up to six months in prison, or deported to France. Gradually, local RDA sections replaced the various GECs, which had also become more Africanised over time. By the early 1950s, most GECs had been absorbed into the structures of the RDA.

In the face of massive colonial repression and the wave of anti-communism in metropolitan France, the unity in the RDA soon broke down. Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the RDA’s first president who would later become president of Ivory Coast, negotiated with the French government in 1950 to secure a political position for himself in exchange for the eviction of Communist members from the movement. On Houphouët-Boigny’s orders, RDA members in the French National Assembly abandoned the PCF’s parliamentary group to integrate themselves into the government’s Centrist group. This betrayal fractured the base of the RDA throughout Africa, and the ten years that followed were marked by strong repression and the ousting of most communist-minded members. The RDA eventually collapsed completely in 1960, as the new independent parties of Africa struggled to agree on a political line for the Rassemblement and future paths of development for their respective countries.

Conclusion

The Groupes d’Études Communistes were a transient phenomenon in the long anti-colonial struggle of the 20th century. They cannot be understood outside of their historical context. The GECs arose in the final phase of the Second World War, when communists, social democrats, and liberals were still united in the international struggle against fascism. Yet as this anti-fascist front broke down in the second half of the 1940s, the staunch anti-colonialism of the communists came into sharp conflict with the pro-imperialist policies of France’s liberals and social democrats. The colonial apparatus was deployed to divide and destroy the GECs and the wider Pan-African movement.

The scarcity of documentation on the GECs and the hostility towards Soviet-aligned organisations in the Third World has meant that the history of these Groupes has long been overlooked, downplayed or simply written off. However, without ascribing them a role and importance that were not theirs, it must be acknowledged that the GECs had a significant influence on the anti-colonial struggle and the development of political parties in Africa. A scan of the long list of militants who were members of these organisations proves this point: Félix-Roland Moumié, Léon M’Ba, François Tombalbaye, Ruben Um Nyobé, Ousmane and Alassane Ba, Modibo Keïta, Abdoulaye Diallo and many others. These figures, who shaped the political history of Africa and the struggle against colonialism, were at various times active in the GECs.

As described above, some of the most prominent members of the GECs and RDA ultimately betrayed the anti-imperialist struggle in Africa in order to secure power for themselves. This reflected the differentiation process that unfolded in the Third World as the anti-colonial struggle advanced. Domestic classes that had hitherto been united in their opposition to colonialism sought to ensure that their own interests would shape the newly independent states. Yet while figures such as Houphouët-Boigny (Ivory Coast) and Léopold Senghor (Senegal) integrated their countries into France’s neocolonial orbit, others such as Sékou Touré (Guniea) and Modibo Keïta (Mali) led the anti-imperialist social revolution in Africa for many years. The GECs not only rallied together a generation of militants, but also helped to organise trade union forces in Africa such as the Union Générale des Travailleurs d’Afrique Noire, Africa’s largest trade union that was founded in 1957 under the leadership of Sékou Touré. If we bear in mind the three primary objectives set by the PCF in 1945 – greater anchoring of the struggle within the local populations, coordination and unity amongst the trade unions, and creation of progressive anti-colonial parties in Africa – then the GECs can be considered as rather successful.

In order to learn more from the valuable experiences of building and sustaining the GECs, it will be necessary to carry out a more in-depth examination: to delve into Suret-Canale’s studies and track down his sources. This short article is an open door to such an approach and looks forward to being built upon.

[1] The CNR was the body that coordinated the resistance groups fighting to liberate France from Nazi occupation. Its political program included communist economic inspiration for a plan of social renewal for the liberated country.

Bianchini, Pascal, Ndongo Samba Sylla and Leo Zeilig. Revolutionary Movements in Africa – An Untold Story. Pluto Press, 2024.

Galeazzi, Marco. “Le PCI, le PCF et les luttes anticoloniales (1955-1975)”, Cahiers d’histoire. Revue d’histoire critique, n.112-113, 2010, pp. 77-97.

Kipré, Pierre. Le Congrès de Bamako ou la naissance du RDA. Éditions Chaka, 1962.

Madjarian, Grégoire. “La Question coloniale et la politique du Parti communiste français (1944-1947)”. Crise de l’impérialisme colonial et mouvement ouvrier. La Découverte, 1977.

Ruscio, Alain. “2. Le PCF et la question coloniale (de 1920 à 1935)”, Les communistes et l’Algérie. Des origines à la guerre d’indépendance, 1920-1962, sous la direction de Ruscio Alain. La Découverte, 2019, pp. 27-53.

Suret-Canale, Jean. L’Afrique Noire, De la Colonisation aux Indépendances. Éditions Sociales, 1977.

Suret-Canale, Jean. LES GROUPES D’ÉTUDES COMMUNISTES (G.E.C) EN AFRIQUE NOIRE. l’Harmaltan, 1994.

III. West Africa in the Grip of Monetary Dependency

Georges Hallermayer, written 9 September 2022, last updated 24 April 2024

For more than ten years now, Africa has been bound up in a “second wave of independence”, striving to gain sovereignty over economic resources after political liberation was secured in the 1960s. In many countries, a national bourgeoisie is replacing the “comprador bourgeoisie”, with some invoking the pan-African legacy of anti-imperialist leaders such as Mali’s Mobido Keïta or Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah. Ideological differences, including the relationship with the People’s Republic of China, often obscure class divisions. Characteristic of this “second wave” is the effort to reconstruct the nation state: in the first stage, to guarantee the security of its citizens, and then to develop a strong economy to combat poverty and mass unemployment. This second stage also includes the controversial debate around national currencies, which is the focus of this article.

A continent in neocolonial dependence

For decades now, the summits of the African Union have been dominated by the debt crisis, which was contrived by the World Monetary Fund and the World Bank, with the political support of the UN administration. This is a credit policy that requires recipients to “implement” structural reforms in return for debt relief. In 2018 and again in 2023, the President of Senegal, Macky Sall, publicly denounced this approach, which has been dubbed the “Washington Consensus”.

In his 1965 work “Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism”, Ghana’s first president Kwame Nkrumah listed the “structural” mechanisms that were used to keep the newly independent states in neocolonial dependency: Firstly, alongside assassinations and military coups, there is direct influence exerted by presidential advisors and special envoys “trusted by donors in important positions”. Secondly, that which is called “developmental aid” and “budget support” are in fact corrupting “payments for the state apparatus”. Finally, there is an invisible “control of monetary transactions with foreign countries through the establishment of a central banking system controlled by the imperial powers.”[1]

One of the most blatant neocolonial instruments is the franc de la Communauté financière africaine, the CFA franc, which is used across West and Central francophone Africa. As the Senegalese economist Ndongo Samba Sylla and French journalist Fanny Pigeaud wrote in their 2021 book “Africa’s Last Colonial Currency: The CFA Franc Story”: “The CFA is more than just a currency. The CFA franc allows France to manage its economic, monetary, financial, and political relations with some of its former colonies, according to a logic that works in its interests.”[2]

Historical “Afrexit” attempts in Guinea and Mali

After Guinea had left the CFA currency union with the Guinean franc in 1960, Charles de Gaulle was unable to prevent Mali’s “Afrexit” in 1962. In neighboring Togo, however, the assassination of President Silvanus Olympio on 13 January 1963 – just two days before the planned exit from the CFA zone – successfully kept Togo in France’s imperialist orbit.[3] Guinea was subsequently punished by Paris with not only “trade barriers”, but also counterfeit Guinea franc notes produced by the French secret service.[4]

Mobido Keïta, President of Mali following the country’s independence in 1960, had tried to develop economic autonomy and pursue a “non-capitalist path of development”[5] by issuing a Malian franc that had been printed in Czechoslovakia. Yet, in 1968, he was ousted by the military under Colonel Moussa Traore and imprisoned for the rest of his life. Nevertheless, it took until 1984 for Mali to be reintegrated into the West African CFA.[6] Mali no longer had to deposit 100 percent of its currency reserves with the Banque de France, as had been imposed before 1973, but only 65 percent. Since 2005, it deposits just 50 percent of its currency reserves in Paris, but an additional 20 percent for “financial liabilities”.[7]

Ghaddafi’s punishment for supporting Afrexit

While the protection of human rights and democracy was the official justification for ostracising Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, this was only a pretext for the West’s military intervention in the country. In leaked emails from April 2011 (subsequently published by Julian Assange), it was revealed why US officials like Hilary Clinton and her close advisor Sidney Blumenthal were so concerned about the Libyan leader: “Qaddafi’s government holds 143 tons of gold, and a similar amount in silver…. This gold was accumulated prior to the current rebellion and was intended to be used to establish a pan-African currency based on the Libyan golden Dinar. This plan was designed to provide the Francophone African Countries with an alternative to the French franc (CFA).”[8]

The email also cites a Source Comment: “According to knowledgeable individuals this quantity of gold and silver is valued at more than $7 billion. French intelligence officers discovered this plan shortly after the current rebellion began, and this was one of the factors that influenced [French] President Nicolas Sarkozy’s decision to commit France to the attack on Libya.”

The mechanisms of exploitation

The French parliamentary advisory body (Conseil économique, social et environnemental) had already reported in its 1970 report on the “indisputable advantages” of the CFA for France – i.e., for French monopoly capital:[9]

-

- The French Treasury (Trésor Public) often charged negative interest on currency deposits. Mali and the other CFA countries therefore hardly received any interest on their deposits; on the contrary, they usually had to pay for them.[10]

- Any capital gains were used as French development aid in the form of loans, which then had to be repaid with interest. However, the CFA countries themselves could not use their own reserves as loan collateral, as they were held by the French Treasury. They therefore had to borrow at market conditions (mainly from France), their creditworthiness rated accordingly and, depending on this, the interest rate set by rating agencies such as Moody’s, Fitch and Standard & Poor’s – which was sharply criticised in 2019 by Macky Sall, the President of Senegal and current Chair of the African Union at a symposium with several West African heads of state.[11]

- French companies operating in the CFA region can freely repatriate their funds without incurring an exchange rate risk.

- France can pay for imports from the CFA countries with its own currency and thus save foreign currency for other commitments – which was particularly advantageous when the French franc was weak and “unstable”.

- By providing CFA franc at a fixed rate, the seigniorage (the difference between the cost of issuing the currency and its face value) effectively flowed to France and the European Central Bank.[12]

Professor Kai Koddenbrock and the Senegalese economist Ndongo Samba Sylla outlined the “winners and losers” of the CFA system as follows:[13]

|

|

Winners |

Losers |

|

Social status |

Upper middle class and upper classes (including central bank executives and political elites)

Benefit from low inflation, a strong currency, the absence of exchange rate risk, and free transferability. |

Popular classes and unskilled workers outside the modern sector, new job seekers

Suffer consequences of deflationary policies: stagnant incomes and low net creation of decent jobs.

|

|

Companies |

Multinational companies and other foreign companies

Benefit from low inflation (low wage costs), the absence of exchange rate risk, and free transferability. |

Local producers and local businesses

Suffer from a scarcity of bank credit and expensive bank interest rates as well as the anchoring to the euro. |

|

Economic sectors |

Trade and other services

Benefit from low inflation and the euro peg (which makes imported products cheap relative to local products). |

Agriculture and industry

Suffer from a shortage of bank credits and expensive bank interest rates as well as a currency overvaluation because of the peg to the euro. |

|

Foreign trade |

Importers

Benefit from the euro peg and the absence of an exchange rate risk. |

Exporters of goods other than primary products

Suffer from a scarcity of bank loans and expensive bank interest rates as well as the euro peg. |

|

Finance |

Banks in the franc zone

Benefit from a situation of oligopoly and high real interest rates.

Financial markets and international banks

Benefit from high real interest rates (notably in a context of zero-interest rate policy in the Global North) and important volumes of illicit financial flows. |

Households, [small and medium-sized enterprises] and states

Suffer from a scarcity of bank credits and expensive bank interest rates. States must rely on external funding to finance development/productive investment.

States

Suffer from the volatility of foreign direct investment and high borrowing costs on international markets. In a context of zero-interest rate policies, states are issuing eurobonds at 6-7 percent while the real returns on their foreign exchange reserves are negative. |

In short, the CFA currency system favors the commercial sector, importers, multinationals, and the middle classes. It hinders the development of industry and agriculture, small and medium-sized local enterprises, and exporters. This reality was shockingly demonstrated in Mali and other countries with the “CFA treaty revision” in 1994, when these states witnessed a 50-percent devaluation of their currency overnight.[14] The public debt soared, and poverty and hardship became entrenched.

Signs of protest and change

The year 2017 brought a breakthrough: on the one hand, protests against the CFA franc took to the streets, culminating in the symbolic burning of a 5,000-franc bill; on the other hand, the political debate about the CFA franc and “La France, dégage !” (France, get out!) intensified.[15] Chad’s late President Idriss Deby Itno had said in 2015 that the CFA was “dragging down African economies” and that it was “time to cut the cord that is preventing Africa from developing.”[16]

Three fronts emerged on the currency issue, as a dossier by Jeune Afrique identified them:[17]

- The “guardians of the temple”, the upholders of the status quo, such as Alassane Quatara, President of Côte d’Ivoire and Lionel Zinsou, Prime Minister of Benin

- The “reformists”, among them the Togolese ex-minister Kako Nubukpo, “Commissaire” at the Bank of Central African States (BEAC), who had to resign as director of the l’Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) due to his well-founded criticism.[18]

- The “iconoclasts” who want to abolish the CFA all together.[19] As the Togolese presidential advisor Dela Apedjinou said: “The African continent must achieve monetary independence. The CFA system stands in the way of this.”[20] Ndongo Samba Sylla is also of the opinion that states should strive for complete sovereignty over their currency. Influenced by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a post-Keynesian school of thought, he believes that West African states could promote more diversified agricultural production and industrialisation through a sovereign monetary policy. However, this alternative approach also shows that a sovereign monetary policy must go hand in hand with other economic policy measures and is a necessary but not a sufficient solution.

The slow end of a colonial currency

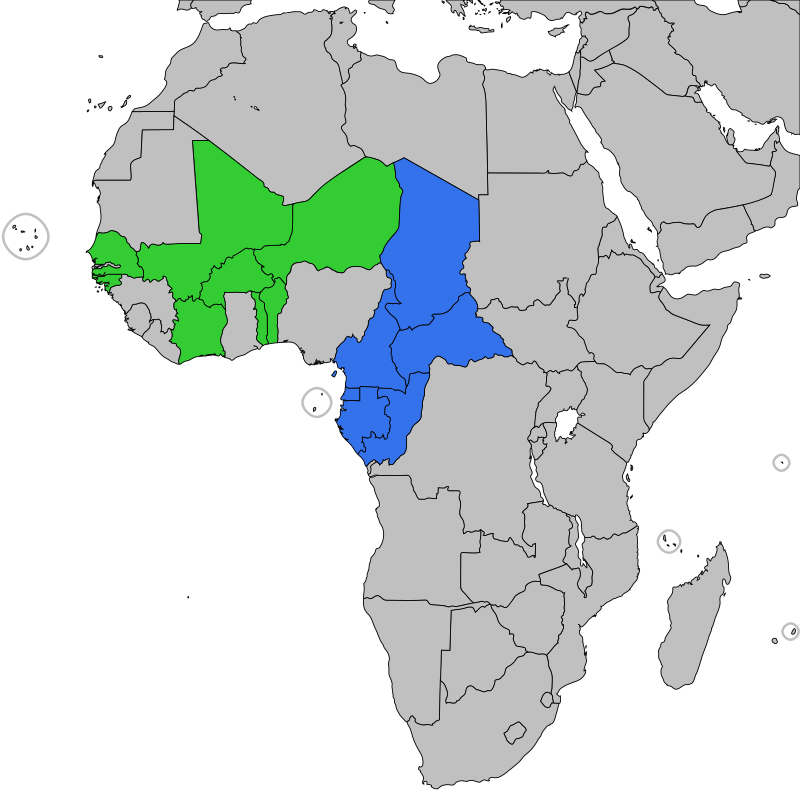

As can be seen from the map of West Africa, the CFA franc separates two currency areas with two separately Paris-oriented central banks: the BEAC (Bank of Central African States) in Yaoundé, Cameroon and the BCEAO (Central Bank of West African States) in Dakar, Senegal.[21]

In 1980, Cameroonian economist Joseph Tchundjang Pouemi published a book entitled “Monnaie, servitude et liberté. La répression monétaire en Afrique” (Money, servitude, and freedom: Monetary repression in Africa), which served to reinvigorate the debate. Currency, Pouemi argued, should no longer be the domain of “specialists” posing as magicians; nothing was more urgent than mobilising public opinion. However, it was not until 1993 that the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) decided to introduce its own currency – the ECO – as a consequence of the CFA treaty revision. The West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA), on the other hand, did not want to give up the CFA franc with the central bank BCEAO in Dakar. The maps above how the CFA franc overlaps with ECOWAS.

At the turn of the millennium, the newly-founded Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) began intensifying efforts towards independent development in Africa. Even if there is no direct connection with the currency debate, the discussion about African integration and national autonomy has been and continues to be influenced by this forum.

The question is not “how to get out of the CFA franc, but above all what currency do we need to transform our economy and society”, as Cameroonian sociologist Martial Ze Belinga put it. “The money we want is a money that serves credit, employment, and ecology. This is a whole agenda, a whole paradigm that is being set in motion and that cannot be the current paradigm, whose rationality is the rentier and predatory economy” (Kako Nubukpo).[22]

In 2000, Ghana, Nigeria, Guinea, Gambia, and Sierra Leone founded the “ECO Zone” (joined in 2010 also by Liberia) to create a common currency. Their national currencies are not pegged to the euro. However, even Africa’s strongest economy, Nigeria, is not in a position to meet the four agreed convergence criteria: price stability, budget deficit, financial reserves and start-up financing.

In 2005, the ECOWAS summit postponed the introduction of a common currency until 2015, but even in the year of the FOCAC in Johannesburg with China’s 60-billion-dollar pledge, the plans remained on the back burner and the introduction was postponed until 2020.

In 2019, the French President Macron and Ivorian President Ouattara took ECOWAS –which had just defined the convergence criteria for a single currency – by complete surprise by having eight West African UEMOA states (Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo) introduce the ECO at the end of 2020. The transfer of parity to the euro was implemented without consultation. The advantage that Paris derives from the CFA was thus de facto extended to Germany, as Kako Nubukpo concluded.[23] The ECO member states, led by Nigeria and Ghana, condemned the unilateral action of the UEMOA states.

Under pressure, Macron conceded two points: To withdraw France’s representative (with veto power) from the CFA central banks and to leave the currency reserves to the central banks themselves. In 2021, ECOWAS once again postponed the introduction of the EU-backed UEMOA-ECO until 2027.[24]

The challenges and possible scenarios

In an interview on 1 September 2020[25], Prof. Kako Nubukpo outlined three major challenges: firstly, to abolish the neocolonial symbolism of the acronym CFA and replace it with an African name; secondly, to determine the appropriate level of integration for a new currency union, e.g., the federal budget and common policies; and thirdly, to find the right level for the exchange of national currencies into the new regional money, for example Nigeria’s naira or Ghana’s cedi. According to him, the most accepted scenario at the moment is the ECO-CFA with a fixed exchange rate to the Euro and the gradual inclusion of ECOWAS states into the UEMOA group (such as Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, etc.), as most of the convergence criteria set for joining the ECO are met by the UEMOA member states.

However, Nubukpo sees a second scenario where convergence is not towards the UEMOA states but towards the ECOWAS member states. A third scenario would offer “monetary coexistence” within the ECOWAS region, with a common ECO naira of the original ECO member states. Finally, a fourth possibility would see “currency duality”, with the ECO as a common currency, but running alongside each country’s national currency.

Given the weakness of the euro as a result of the sanctions crisis – the CFA franc lost 24% against the franc guinéen between August 2021 and August 2022[26] – but also due to the dedollarisation of the BRICS countries in particular, the discussion about the anchor currency for the ECO, but also about issuing a national currency of its own, will be further fuelled, even if the Banque de France emphasises that the robustness of the CFA franc in West and Central Africa has helped to absorb some of the successive economic shocks.[27] In Nigeria, the scarcity of cash during the reissue of the naira has gone so far that the CFA franc is used as a currency for commercial transactions in the border regions with Benin, Cameroon, and Niger and has been officially accepted since February 2023.

The disputes about economic autonomy, shaking off neo-colonialist dependency and, in particular, Africa’s monetary development path are hotly debated beneath the surface. Could a single currency encompassing the West African economic union ECOWAS be a further step towards implementing the African Free Trade Area AfCFTA? Or will the proponents of a national currency prevail in order to develop cooperatively in a multipolar world?

What happens next will be decided not only in West Africa. The Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) has also decided to stop using the CFA franc and intends to completely close the operating account at the Banque de France, where it currently holds only 50% of its foreign exchange reserves. French representatives on the decision-making and supervisory bodies of the BEAC, the regional central bank, are to be removed.

The Alliance of Sahel States – the dream of independence

A series of military coups in West and Central Africa have also shaken up this debate. The transitional governments in Chad, Guinea, and Gabon have come to terms with the neocolonial power France in negotiations and were subsequently largely recognized by ECOWAS for their course “back to democracy”. In stark contrast, ECOWAS has tightened the economic sanctions against Mali and Burkina Faso since 2020. ECOWAS even considered intervening militarily against Niger’s new government. In the face of this real danger – Senegal was gun ready, and Benin granted Nigeria’s army the right of passage into Niger – Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger concluded a mutual assistance pact on 16 September 2023. This “Liptako-Gourma Charter” founded the “Alliance des États du Sahel” (Alliance of Sahel States, ASS), which provides for the establishment of an “architecture of collective defence and mutual support”. The first summit at ministerial level took place on 25 November 2023 in Mali’s capital Bamako. The ministers adopted eighteen recommendations to promote political and economic integration, for example, to secure the free movement of people and goods and to promote industrialisation. Their declaration announced the establishment of a joint stabilisation fund, a joint investment bank and the intent to form a confederation.[28]

In December 2023, the interim president of Burkina Faso again spoke of the establishment of a monetary union and the creation of a confederation. This would realise the dream of sovereignty and finally put an end to the eleven clauses of the colonial treaties signed with France at independence on 26 December 1959 (occupation troops, CFA franc, confiscation of national currency reserves, French official language, etc.).

Although foreseeable, the news that the ASS would leave the ECOWAS hit like a bombshell on 28 January 2024 (although this could only be realised in a year’s time according to the ECOWAS statutes). Denis Sindete, editor-in-chief of “La Flamme”, the organ of the Benin Communist Party PCB, reported enthusiastically that a solidarity fund had been set up in Niger.

There is also turbulence on the financial market. Burkina Faso was forced to postpone the issue of government bonds worth 58 billion dollars indefinitely. Investors were only prepared to subscribe to around half of the amount. The rating agency Moody’s is already seeing a boomerang effect for West African banks.

The question of a national or common currency

Mali is currently hesitating to drop the CFA franc: Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop confirmed on 1 February 2024 that the country would remain in the UEMOA. The experience with the financial sanctions imposed by the central bank BCEAO, which cut Mali off from its own financial system, is likely to have played a role in Mali immediately declaring that it would remain in the Union. Burkina Faso’s Ibrahim Traore, on the other hand, is still considering withdrawing from the CFA franc. What continues to unite the three ASS states is the issue of protecting their borders and combatting terrorist groups in the region.

A commission of experts was set up at the ASS summit in November 2023. Its remit is to examine the introduction of a common currency. A separate central bank would have to be established and the convertibility of the currency guaranteed through gold backing or foreign exchange. The agreed monetary policy would have to decide between a fixed exchange rate or a freely convertible rate. Technical issues such as the production of banknotes, the minting of coins etc. would have to be clarified. The Council of ASS Ministers had proposed a stability fund to secure public finances and cushion price increases. An investment bank should ensure the attractiveness of the ASS for foreign investors. In its recommendations, the expert commission must weigh up the risks against the expected economic benefits: the seigniorage (the difference between the value of money and the cost to produce and distribute it), interest credits from the foreign exchange reserves, improved credit rating, active growth policy, etc. Of course, the “protective shield” of the euro peg, which has so far prevented blatant inflation and exchange rate fluctuations on the money market, would be removed.

According to Yves Ekoué Amaizo, Director of the Afrocentricity Think Tank and Professor Nicolas Agbohou, implementation is a lengthy process that would have to follow three parallel paths: On the one hand, creating a monetary ecosystem with a domestic and an external currency backed by commodities (gold). Secondly, independent currency, banking, and financial institutions need to be established. The focus here should be on digitalisation and securing transactions. Thirdly, a payment channel outside the SWIFT system should be chosen without refusing to use the SWIFT system. It is a matter of arming oneself against possible sanctions.[29]

Leaving the UEMOA would be associated with an increase in import costs. The exchange of the CFA franc into the “ECO”, which is still dependent on Paris and has been postponed to 2027, is unlikely to play a role in the discussion, nor is the pan-African currency that the African Union is striving for. Developments in Zimbabwe, on the other hand, are likely to have an influence on the discussion in the ASS, albeit indirectly. Zimbabwe is making its sixth attempt since 2008 to permanently establish its national currency – and this time it is gold-backed.[30] The issue in May of ZiG banknotes in the amount of 100 million ZiG is intended to replace the worthless Zimbabwe dollar, even if the US dollar continues to be used as legal tender. The election of Bassirou Diomaye Faye as president in Senegal – with Ousmane Sonko as Prime Minister – has also further revitalized the debate and increased the likelihood of Senegal opting to leave the CFA franc.

In summary, leaving the CFA franc and throwing off the “neo-colonial chain” (Kwame Nkrumah) to achieve economic sovereignty must be well prepared.

Stephane Sèjourné, France’s foreign minister, told the media on 8 April 2024: “We are no longer in governance, we no longer have reserves in France to ensure the convertibility of the currency… If African countries agree to change the name and organise their monetary organisation differently, that is the sovereignty of the states, and we want to accompany this movement well.” France is pretending to stay out of the debate: “It is not for France to have an opinion on this. We have done our part by withdrawing from CFA governance, now it is up to the African states to decide.”[31]

However, the visit by General Michael Langley, the commander of the United States Africa Command (Africom), at the beginning of May to Benin – a UEMOA member state and a direct neighbour to Niger and Burkina Faso – is just a further indication that the struggle for economic sovereignty will still be a long and contradictory process.

[1] Kwame Nkrumah: Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism. New York 1965.

[2] Fanny Pigeaud/Ndongo Samba Sylla: Africa’s Last Colonial Currency: The CFA Franc Story. London 2021.

[3] Koffi de Lome: “Opinion: Sylvanus Olympio’s assassination two days before he withdrew Togo from the CFA franc zone”, in: Face2Face Africa 21. Jan. 2019. Godwin Tete: “Le Franc CFA et l’assassinat de Sylvanus Olympio”, in: cvu-togo-diaspora 19. Jan. 2017.

[4] Fanny Pigeaud/Ndongo Samba Sylla: Africa’s Last Colonial Currency: The CFA Franc Story. London 2021.

[5] Author’s collective: “Afrika vom Zusammenbruch des imperialistischen Kolonialsystems bis zur Gegenwart”, in: Geschichte Afrikas. Akademie-Verlag Berlin 1984, pp. 72-77.

[6] A first sign of intellectual resistance can be seen in Joseph Tchundang Pouemi: “Monnaie, servitude et liberté. La répression monétaire en Afrique”, in: Jeune Afrique, 1980, 2nd edition in 2000.

[7] Anis Chowdry, Jomo Kwame Sundaram: “Neo-colonial currency enables French exploitation”, in: Monthly Review August 2022.

[8] Wiki leaks: https://wikileaks.org/clinton-emails/emailid/12659

[9] Anis Chowdhury, Jomo Kwame Sundaram: “Neo-colonial currency enables French exploitation”, in: Monthly Review August 2022.

[10] With the disposal of its own foreign exchange reserves, this expropriation has become obsolete.

[11]The Africa Report 6. Dec. 2019: “Forget the Washington Consensus, meet the Dakar Consensus”.

[12] The seignorage now flows via the central banks of the BCEAO and BEAC region to the tax authorities in accordance with the distribution regulations. See Rohinton Medhora: “The allocation of seigniorage in the Franc Zone: The BEAC and BCEAO regions compared” in Word Development, Volume 23, Issue 10, S. 1639 – 1824 (October 1995).

[13] Kai Koddenbrock, Ndongo Samba Sylla: “Towards a Political Economy of Monetary Dependency. The Case of the CFA Franc in West Africa”, Maxpo discussion paper No. 19/2, pp. 21 – 24.

[14] As part of the “CFA treaty revision”, the CFA was devalued by half on 12 January 1994 at the request of the International Monetary Fund. This happened overnight, without consultation, without exception, following a simple notification from the Banque de France. Multinational corporations were subsequently able to buy mineral resources such as uranium and gold, as well as crops such as coffee and cocoa, at incredibly low prices. African exporters had to survive the threat of ruin. Imports such as fertilisers, machinery, and electronic devices were instantly overpriced. Further public debt was inevitable, as was the privatisation of state-owned companies. This was pure neoliberalism.

[15] Razia Athman: “Widening protests against the CFA franc rage on”, Business Africa 18. Sept. 2017.

[16] Cited in Vijay Prashad, Kambale Musavuli: “Keine Marionetten mehr”, in: Junge Welt 2. Aug. 2023.

[17] Jeune Afrique: “[Infographie] Franc CFA: les personnalités, qui animent le débat”, 21. June 2019.

[18] Kako Nubukpo: “Le sommet Afrique-France sera l’occasion de poser les questions qui fâchent”, in: Jeune Afrique 27 April 2021, alongside Carlos Lopez, former Secretary of the UN Commission for Africa, but also Dominique Strauss-Khan, former Director General of the World Monetary Fund.

[19] Kako Nubukpo, Martial Ze Belinga, Demba Moussa Dembele and Bruno Tinel: “Sortir l’Afrique de la servitude monétaire. A qui profite le franc CFA?”, Paris 2016. In addition to Ndongo Zambia Sylla, the former parliamentary president Mamadou Koulibaly and Nicolas Agbohou from Côte d’Ivoire, as well as the pan-Africanist Kemi Seba from Benin, are also in favour of abolishing the CFA.

[20] Dela Apedjinou: “Eine polarisierende Währung. Die Debatten um den CFA-Franc”, in: WeltTrends Mai 2021, pp. 37 – 41.

[21] Nadoun Coulibaly: “Franc CFA-Euro: la parité fixe, facteur de la résilience des économies de l’Uemoa et de la Cemac“, in: Jeune Afrique 15. Nov. 2022.

[22] Joel Te-Lessia Assoko: “‘Une histoire du franc CFA’, ce passé qui ne passe plus“, in: Jeune Afrique 27. Jan. 2023.

[23] Cited in the documentary by Sengalese Katy Lena N’daye “Une histoire de franc CFA, l’argent, la liberté”, which was broadcast on the LCP channel.

[24] Kako Nubukpo: “Le sommet Afrique-France sera l’occasion de poser les questions qui fâchent”, in: Jeune Afrique 27. April 2021. Alain Faujas: “La vie sans le franc CFA: l’Afrique de l’Ouest est-elle prête?“, in: Jeune Afrique 26. Aug. 2021. Joël Té-Léssia Assoko: “Cedeao: la réforme CFA/eco, victime collatérale du Covid-19“, in: Jeune Afrique 27. Jan. 2021.

[25] Folashadé Soulé, Camilla Toulmin: “Professor Kako Nubukpo: COVID-19 Shows that Global Value Chains Shouldn’t Keep Africa in Chains of Dependence”. Institute for New Economic Thinking 1. Sept. 2020.

[26] Agence Ecofin 18. Oct. 2022: “UEMOA: le FCFA a perdu 24% de sa valeur par rapport au franc guinéen entre août 2021 et août 2022”.

[27] Nadoun Coulibaly: “Franc CFA-Euro: la parité fixe, facteur de la résilience des économies de l’Uemoa et de la Cemac”, in: Jeune Afrique 15. Nov. 2022.

[28] Agence Ecofin 1. Feb. 2024: “Le Burkina Faso pourrait ‘se attaquer’ au franc CFA et quitter l‘UEMOA (Ibrahim Traoré)”.

[29] Mediapart 15. Feb. 2024: “Afrique- AES: Bientôt une monnaie commune au sein de l’Alliance des Etats du Sahel? ”.

[30] Le Monde Afrique 10. April 2024: “Au Zimbabwe, début chaotique pour le ZiG, nouvelle monnaie officielle”.

[31] Agence Ecofin 9. April 2024: “La France ‘a fait sa part du chemin en sortant de la gouvernance du fcfa’ (Stéphane Séjourné)”.

IV. Niger-Sahel: Interference on Hold

Raphaël Granvaud, first published by Survie on 27 February 2024

As it did in Mali and Burkina Faso, France is reaping what it has sown. The failure of its ‘war on terror’ and the incurable paternalism of the French authorities have strengthened popular mobilisation against the French military presence.

On the eve of the 26-27 July 2023, Niger’s President Mohamed Bazoum was overthrown in a military coup led by General Abdourahamane Tiani, head of the Presidential Guard, who was joined by the former Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces, General Salifou Mody. Other army officers rallied them to, in their words, ‘avoid a bloodbath’. The putschists took power under the name of the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (Conseil national pour la sauvegarde de la patrie– CNSP). These events echo the episodes that took place a few months prior in Mali and Burkina Faso, even if each situation has its specificities. In Niger, according to various publications, General Tiani feared that he would be removed from his post himself, following the dismissal of General Mody in April. Bazoum also reportedly asked him to account for the funds earmarked for particular actions by the Presidential Guard, which he enjoyed more freely under the previous president, Mahamadou Issoufou, who remained close to him. Issoufou’s ambiguous attitude, reported several times after the coup was announced, also fuelled suspicions about his initial complicity with the putschists. Although Issoufou had made Bazoum his successor, the latter’s desire to regain control of oil revenues represented a particular source of tension.

A shared context

Over and above the motivations of the players, a similar context seems to have facilitated the coups d’état in the three countries (four if we include Chad, where an unconstitutional dynastic succession was not considered a coup de force by the French embassy). It is probably not entirely coincidental that these coups d’état have taken place in countries in the grip of jihadist insurgencies, partly because of the security threats they pose to states, but primarily as a result of the fact that over the last decade they have been engaged in the ‘war on terror’ alongside France. The almost exclusively security-based approach that has prevailed, sometimes imposed from outside against national rationales, has failed to defeat jihadist groups, and has even allowed them to recruit more people. On the other hand, it has helped to reinforce the role, power, and political importance of the military. In all three countries, the coup plotters benefited from the discrediting of the civilian regimes, which were judged to be corrupt, incapable of responding to the social and security crises affecting a growing proportion of the population, and considered to be primarily subservient to Western interests. This disparagement has been fuelled by the failure of foreign military intervention, to which African presidents have – more or less willingly – appealed. While it cannot be said that the seizures of power were directly targeted against France’s military presence and interference, the incurable paternalism of the French authorities then precipitated the ruptures, and all the more so as the rejection of France’s African policy has become a very effective fuel for mobilising African citizens who want to do away with the most visible mechanisms of neo-colonial domination (military tutelage, the CFA franc, political interference). In the language of the French press, this amounts to using France as a ‘convenient scapegoat’ (LeMonde.fr, 03/09/2023).

France and ECOWAS for war

Over the past two decades, the French administration has got into the habit of hiding behind the positions of the African Union and African regional institutions… at least as long as these are in line with its interests. Thus, the Quai d’Orsay began by ‘firmly condemning any attempt to seize power by force’ and ‘associated itself with the pleas of the African Union and ECOWAS [Economic Community of West African States] to re-establish the integrity of Niger’s democratic institutions’.[1] The following day, President Macron in turn condemned the coup ‘in the strongest possible terms’ and announced that a Defence Council would be held at the Élysée Palace on 29 July, after which budgetary aid to Niger was suspended. Yet the French government is never sufficiently pleased to simply support African institutions. On the one hand, it tries to influence their decisions, and on the other, it never refrains from imposing its own interpretation on them. The Macron presidency was no exception to the rule.

ECOWAS is certainly not a simple transmission belt for French imperialism, but France does have a number of allied heads of state on which it can rely. Although France does not formally take part in ECOWAS debates; it behaves almost like one of its members. Prior to and following the summit in Abuja on 30 July, the French President met with numerous heads of state to press his position. In addition to converging interests with certain francophone countries such as Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, France’s desire to see the most severe economic sanctions and the principle of the use of force to re-establish constitutional legality in Niger adopted was in line with the position of the Nigerian President, who holds the rotating presidency of the organisation. The credibility of ECOWAS was at stake, following its decision in late 2022 to create a (still virtual) regional force to combat coups d’état and terrorism.

On the eve of the summit on Niger, the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (CNSP) denounced a ‘plan of aggression against Niger’ and, during the event, Nigerien demonstrators violently attacked the French embassy. The CNSP justified this action by ‘resentment following the destabilising attitude of a Western chancellery’. On national television, its spokesman also accused France of having sought, ‘with the complicity of certain Nigeriens’, to ‘obtain the necessary political and military authorisations’ to launch a military operation on the presidential palace (Press release 30/07/2023). The newspaper Le Monde (31/07/2023) saw this as nothing more than a ‘hyperbolic accusation to which no one has deemed it appropriate to respond at this stage’, in the same way that the putschists’ warnings following the landing of a French military aircraft on the airport tarmac two days earlier were, in its view, nothing more than ‘paranoia’. Three weeks later, however, journalists from the French daily published a new investigation confirming that ‘a request for intervention was made to the French in Niamey in the hours following the coup (…), and that this request was seriously considered’ by the French authorities. An adviser to President Bazoum commented: ‘They told us that they were in a position to carry out the operation, that it would not affect the President. But the President, who believed that a negotiated outcome was still possible, decided against it. Moreover, ‘between the time when the request was made and the moment when the French could have intervened, some of the loyalists had gone over to the side of the putschists’. Paris had therefore also become ‘reticent’, reports Le Monde (19/08/2023).

French interests

Despite the denials of the French Minister of Foreign Affairs on BFM-TV (31/08/2023), France had not abandoned the path of a military solution. Assured of French support, the ECOWAS heads of state decided on 30 July to not only impose an immediate economic blockade on Niger, but also to issue a one-week ultimatum to get President Bazoum back in office, failing which ‘all necessary measures’ would be taken, including ‘the use of force’. The same day, in response to the actions against the embassy, the Élysée Palace issued a statement promising an ‘immediate and intractable’ response to ‘anyone attacking French nationals, the army, diplomats, and French installations’. President Macron ‘will not tolerate any attack against France and its interests’, it said. French interests in Niger are essentially twofold: uranium and military presence. To date, only one Orano (formerly Areva) mine remains in operation. However, the French company still has another deposit, Imouraren, described as the second largest on the African continent, but whose low uranium content makes it unprofitable to exploit if market prices are too low. Orano is currently looking into the possibility of extracting the uranium by pumping it out after spraying with acid, based on the In-Situ Recovery (ISR) method used in Kazakhstan. Furthermore, while France’s civil nuclear industry has diversified its supplies, uranium for military use still seems to come entirely from Niger. In terms of military presence, France kept 1,500 soldiers still engaged in the ‘war on terror’ after the end of Operation Barkhane.

On 1 August 2023, France evacuated its nationals from Niger, giving credibility to the prospect of a military intervention launched with its support. Two days later, the CNSP announced that it was breaking off the existing military agreements between Niger and France, thereby calling for the departure of the French troops present in the country. This request was deemed null and void by the Élysée, which considered that President Bazoum, who had refused to resign, was the only legitimate authority able to make such a request. On 5 August, on the eve of the expiry of the ECOWAS ultimatum, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs invited the people of Niger to ‘take very seriously’ the threat of regional intervention. On 10 August, following a new summit, ECOWAS announced the ‘immediate deployment’ of its ‘standby force’ (which in reality existed only on paper), but nevertheless said it favoured a diplomatic resolution of the crisis. Paris immediately made known its ‘full support for all the conclusions adopted’.

One-upmanship and diplomatic isolation

It is now rather clear, however, that the bellicosity and arrogance of the French authorities have had a counter-productive effect, even on its closest partners. Firstly, because France’s diplomatic stance greatly helped the military putschists to gain a legitimacy and popular support that they did not initially have. Initially, well-known human rights defenders, anti-imperialist and anti-corruption activists, including those who had tasted repression and imprisonment under Issoufou and Bazoum, criticised or condemned the coup. But faced with the risk of military aggression posed by ECOWAS and France, the mobilisations against the French military presence and in defence of the new authorities merged and reached a growing proportion of the political class, civil society organisations, and the population. At the beginning of September, as tensions between Niger and France reached a climax, tens of thousands of Nigeriens demonstrated in Niamey to demand the departure of the French troops. Niger, which had long been presented as a model of democracy by the French authorities, was in reality a regime riddled with corruption (something not unique to Africa), which easily used repression against opponents, and in which electoral irregularities were not absent. This also partly explains, as in Mali and Burkina Faso, the popular support given to the military despite the repressive measures taken in these three countries, particularly against the press, and the risk of a long-term seizure of power.

In this situation, France’s Western partners in the Sahel quickly decided to let it go it alone, for fear that their presence would also be rejected. In his famous speech to the ambassadors, Macron denounced the abandonment of his allies and mocked the voices that ‘from Washington to the European capitals (…) were explaining that they should not do too much, as it was becoming dangerous’. The European Union readily endorsed the policy of economic sanctions, but refused to support military intervention. European countries fear that they will no longer be able to use Niger, one of the pivotal countries in the outsourcing of Europe’s policy of repression of migrants. In 2015, for example, the EU put pressure on Niger to enact a bill, ‘partly drafted by French officials’ (Le Monde Diplomatique, 01/07/2019), criminalising economic activities linked to the reception and transport of migrants, even though freedom of movement is theoretically guaranteed within ECOWAS. The possibility of a new conflict in the region is also seen as a risk of increasing migration to Europe.

The US State Department, for its part, has from the outset used rhetorical contortions to avoid talking about a coup d’état, which would legally imply a suspension of security cooperation, and has adopted a more flexible stance so as not to break off dialogue. At the beginning of August 2023, President Biden’s staff also informed France and ECOWAS that no financial or logistical support would be given to any military intervention, and then publicly stated that the US did not wish to end its partnership with Niger after having invested ‘hundreds of millions of dollars’ in its military bases. Since then, US drones have resumed their surveillance of the region. Military activity in the Sahel is not considered a priority by the United States, but it is also a question of not letting the new authorities in Niger seek support from the Russians. It would be wrong to think that the US and other European countries deliberately pushed the French military out. The division of labour that prevailed – operational risks for the French, cooperation, logistical support and the provision of intelligence for the others – had suited them until then. But the rejection of the French presence is leading them to put their own interests first and to review the partnerships they have forged with France. The retaliation measures recently adopted by France against Sahelian artists and students, who have been banned from entering the country, will further increase popular hostility towards the French authorities.

What are the prospects?

As expected, after being driven out of Mali and then Burkina Faso, France was forced to announce the closure of its military base in Niger. Officially, this possibility was not on the agenda until the end of September 2023. However, the French Ministry of Defence initially admitted, off the record, that discussions had been initiated to organise the ‘redeployment’ of some of the French military personnel reduced to technical lay-offs. Finally, after several weeks of an almost complete blockade of the French embassy and military base, Macron was forced, in a televised speech on Sunday, 24 September 2023, to announce the withdrawal of his ambassador and French soldiers before the end of that year, so that they would not remain ‘hostages of the putschists’. A victory for the military in power and the Nigerien demonstrators who took turns outside the French enclaves. In return, France is likely to increase its cooperation and military presence in other countries also threatened by jihadist groups (Togo, Benin, Ghana, Guinea and Senegal). But the closure of the military base in Niger, following on from those in Mali and Burkina Faso, provides an opportunity to impose on the public debate the demand for a withdrawal of all French military forces from Africa, and an end to all interference. In a sign of the times, the media philosopher Achille Mbembe, who in his report submitted to Macron at the end of the Africa-France summit in Montpellier forgot to recommend the closure of French bases and the end of the CFA franc, is now remembering this. If you read the French press on the latest developments, you can already sense a wave of panic among certain editorialists and many politicians who are calling for an urgent reform of France’s African policy – in order to avoid losing all influence. The same people are happy to blame the loss of influence in the Sahel on Russian disinformation, without realising that the success of propaganda on social media and the presence of Russian flags at demonstrations are the symptoms, not the cause, of the rejection of France’s African policy. We must hope that a new era is dawning, but beware of claiming the victory too soon.

On the one hand, we must remember that it is in times of crisis that French imperialism deploys its strongest and most violent capacity to cause harm. The people of Côte d’Ivoire remember this, particularly in Abidjan in 2004 and 2011. France’s African policy must therefore be completely disarmed. But the idea that France’s ‘greatness’ and ‘historic responsibility’ on the international arena must be maintained, and can only be achieved by continuing to act as the guardian of order in French-speaking Africa, is deeply rooted in the French political class. On the other hand, a true assessment can only be made at the end of a rather long period: over the course of its history, the French military presence in Africa has, depending on the country, experienced sometimes unexpected turnarounds. Moreover, the military instrument is only one of the means used to maintain relations of domination, while the economic and financial tools, starting with debt and the CFA franc, remain formidably effective. Finally, the repeated speeches about the death of Françafrique have often had the effect, if not the objective, of masking these mechanisms, slowing down awareness and preventing the mobilisation that is still so necessary.

[1] Statement by the spokeswoman for the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, 26/07/2023.

By Raphaël Granvaud. This article was initially edited and published by Survie on 27 February 2024, and has been made available by the author and the collective in solidarity with the Zetkin Forum. Survie is an association that advocates and fights for resistance to French neo-colonialism in Africa and leads various campaigns and actions with a wide scope on the continent. More information can be found at survie.org